Good governance underscores three crucial pillars: transparency, accountability, and responsiveness within the administration.

The “Citizen’s Charters” initiative serves as a direct response to the everyday challenges faced by citizens when engaging with organizations that provide public services. This concept embodies the foundation of trust between service providers and their users.

The concept initially took shape and was implemented in the United Kingdom under the Conservative Government of John Major in 1991 as a National Programme. Its primary objective was to continually enhance the quality of public services, ensuring they align with the needs and preferences of the people. Subsequently, it saw a re-launch in 1998 under the Labour Government of Tony Blair, rebranded as “Service First.”

Six Principles of Citizen’s Charters

1. Quality: Improving the quality of services;

2. Choice: Providing choice wherever possible;

3. Standards: Specify what to expect and how to act if standards are not met;

4. Value: Add value for the taxpayers’ money;

5. Accountability: Be accountable to individuals and organisations; and

6. Transparency: Ensure transparency in Rules/Procedures/Schemes/Grievances.

International scenario

In 1993, the Malaysian Government introduced Guidelines on the Client’s Charter. These guidelines aimed to aid government agencies in creating and enacting the Client’s Charter. This charter represents a written pledge from an agency to deliver services and outputs in line with predetermined quality standards.

The Commonwealth Government of Australia initiated its Service Charter in 1997, aligning with its ongoing dedication to enhancing the quality of services provided by agencies to the Australian public. This initiative aimed to shift government organizations from bureaucratic procedures to outcomes that prioritize the needs of the customer.

Furthermore, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat launched its Service Standard Initiative in 1995, drawing inspiration from the United Kingdom’s Citizen’s Charters but expanding its scope significantly. This initiative was designed to address a broader array of standards and commitments.

Indian scenario

Since 1996, there has been a noticeable shift in public expectations, with citizens desiring not only a responsive government but also one that can anticipate their needs. This evolving sentiment led to a consensus within the government on the importance of effective and responsive administration.

In a significant event, the Conference of Chief Ministers from various States and Union Territories convened in New Delhi on May 24, 1997, under the leadership of the Prime Minister of India. During this gathering, an “Action Plan for Effective and Responsive Government” was adopted, focusing on both the central and state levels. A key decision made at this conference was the initiation of Citizen’s Charters, starting with sectors that have a substantial public interface, such as Railways, Telecom, Posts, and Public Distribution Systems.

These Charters were expected to define service standards and reasonable timeframes for public expectations, while also providing avenues for grievance redress and an element of independent oversight, involving citizen and consumer groups.

To drive this initiative, the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances within the Government of India (DARPG) took on the task of coordinating, formulating, and implementing Citizen’s Charters. They communicated guidelines for creating these Charters and provided a list of best practices and potential pitfalls to various government departments and organizations, facilitating the development of focused and effective charters.

The Citizen’s Charters are expected to encompass several essential elements, including

- Vision and Mission Statement: A clear articulation of the organization’s overarching goals and purpose.

- Details of Business Transactions: Information about the nature of activities and transactions conducted by the organization.

- Client Information: Identification and description of the various client groups served by the organization.

- Services to Clients: An outline of the services provided to each client group, ensuring transparency and clarity.

- Grievance Redress Mechanism: Information on how individuals can access the grievance redress mechanism, making it accessible and understandable.

- Client Expectations: Expectations or obligations from the clients or users, representing a distinctive addition to the Indian Citizen’s Charter, adapted from the UK model.

This Indian adaptation of the Citizen’s Charter model primarily inherits the structure from the United Kingdom but introduces the unique component of outlining ‘expectations from the clients’ or, in other words, ‘obligations of the users’.

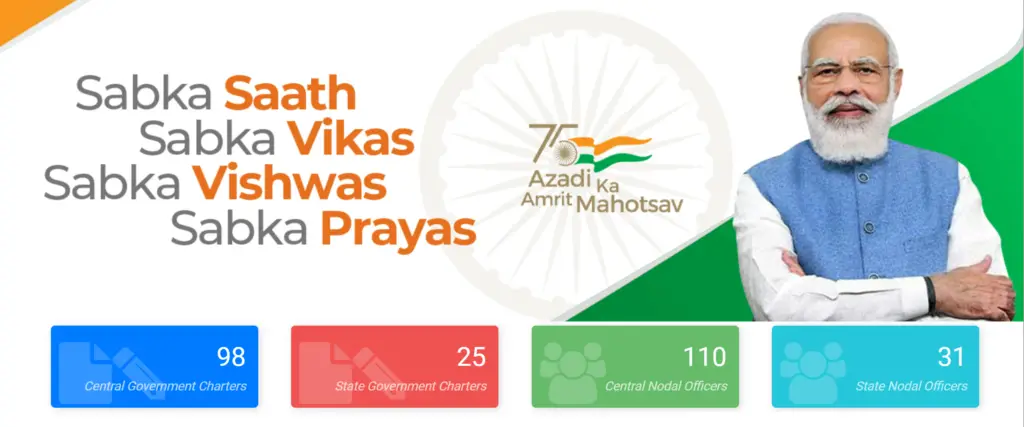

Website’s on Citizen’s Charters

The Government of India has created a comprehensive website dedicated to Citizen’s Charters, which can be accessed at www.goicharters.nic.in. Launched by the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances on May 31, 2002, this website serves as a central repository for Citizen’s Charters issued by different Central Government Ministries, Departments, and Organizations. It offers a wealth of valuable information, data, and relevant links to facilitate easy access and understanding of these Charters.

Implementation of Citizen’s Charters

The decision to initiate this endeavor focused on the banking sector, taking into consideration the second phase of economic reforms. The banking sector was chosen as it had made significant strides in customer service and had effectively utilized information technology to streamline various processes. The central aim of this initiative was to establish the banking sector as a benchmark for excellence in implementing the Citizen’s Charter.

To kick-start this effort, three prominent national-level banks—Punjab National Bank, Punjab and Sind Bank, and Oriental Bank of Commerce—were chosen for a guidance program by the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances (DARPG) in the year 2000.

Problems in Implementation

- The prevailing belief within organizations that crafted Citizen’s Charters was that this task was simply a top-down directive, with limited or absent consultation processes. Consequently, it became a routine activity lacking clear focus.

- Successful implementation of any Charter hinges on adequately trained and oriented employees who understand the spirit and content of the Charter. Unfortunately, in many cases, the relevant staff lacked sufficient training and awareness.

- Instances of officer transfers and reshuffles at critical stages of Citizen’s Charter formulation and implementation disrupted the strategic processes in place, impeding the initiative’s progress.

- There was a lack of systematic awareness campaigns aimed at educating clients about the Charter.

- In certain cases, the service standards and timeframes set in Citizen’s Charters were either too lenient or overly stringent, leading to unrealistic expectations and dissatisfaction among Charter clients.

- The fundamental concept behind Citizen’s Charters was not always comprehended accurately.

- Some organizations mistakenly considered previously produced information brochures, publicity materials, or pamphlets as equivalent to Citizen’s Charters.

Lessons need to be consider

- It’s natural for both bureaucrats and citizens to initially view the Citizen’s Charter initiative with skepticism, as is the case with any new endeavor. Overcoming this skepticism requires a well-designed and creatively delivered awareness campaign that targets all stakeholders effectively.

- The issuance of a Citizen’s Charter doesn’t bring an overnight transformation in the long-established mindsets of staff and clients. Consequently, persistent and consistent efforts are essential to foster attitudinal changes.

- New initiatives often encounter resistance and apprehension among staff, especially those at the forefront. Involving and consulting with them at every stage of Citizen’s Charter formulation and implementation can help mitigate this resistance and turn them into equal partners in the process.

- Rather than attempting to revamp all processes simultaneously, it’s advisable to divide them into smaller, manageable components and address them one by one.

- The Charter initiative should incorporate a built-in mechanism for monitoring, evaluating, and reviewing Charter performance, preferably involving an external agency.

Evolution of Citizen’s Charters

The evaluation of various government agencies’ Citizen’s Charters was conducted by DARPG and the Consumer Coordination Council, a New Delhi-based NGO, in October 1998.

In the fiscal year 2002-03, DARPG enlisted the expertise of a professional agency to develop a standardized model for both internal and external evaluation of Citizen’s Charters. This model aimed to provide a more effective, quantifiable, and objective assessment.

According to the evaluation report compiled by the agency, the major findings were as follows:

- In the majority of cases, Charters were not formulated through a consultative process.

- Service providers, for the most part, lacked familiarity with the philosophy, goals, and main features of the Charter.

- Adequate publicity for the Charters had not been given in any of the evaluated Departments. In most Departments, the Charters were only in the early stages of implementation.

- No specific funds had been allocated for awareness generation related to the Citizen’s Charter.

Suggestions

- Involving citizens and staff at every stage of the Charter’s development.

- Providing staff with proper orientation regarding the Charter’s key features, departmental vision and mission statements, and essential skills like team building, problem-solving, grievance handling, and communication.

- Establishing a comprehensive database to track consumer grievances and their resolution.

- Enhancing the Charter’s visibility through a variety of means, including print media, posters, banners, leaflets, brochures, local newspapers, and electronic media.

- Allocating specific budgets for generating awareness and staff training.

- Learning from and replicating best practices in this field to continually improve the Charter’s impact.