CLICK HERE TO GO TO FUNCTIONS AND FORMATION OF JET STREAM AND IT’S APPLICATIONS

The Polar Vortex

The polar vortex, sometimes called a circumpolar vortex or polar cyclone, is a distinctive meteorological phenomenon. It manifests as a massive, cold, upper tropospheric air parcel, often extending into the lower stratosphere. This cyclonic (low-pressure) system sprawls across the polar region during winter, diminishing strength when summer arrives.

What sets polar cyclones apart from their counterparts is their year-round presence. They are not confined to any specific season and can materialize suddenly, sometimes forming in less than 24 hours. Their path and movement remain highly unpredictable, with durations ranging from a single day to several weeks. These cyclones are most frequently generated above northern Russia and Siberia.

Polar Vortex Cold Waves and Stratospheric Warming

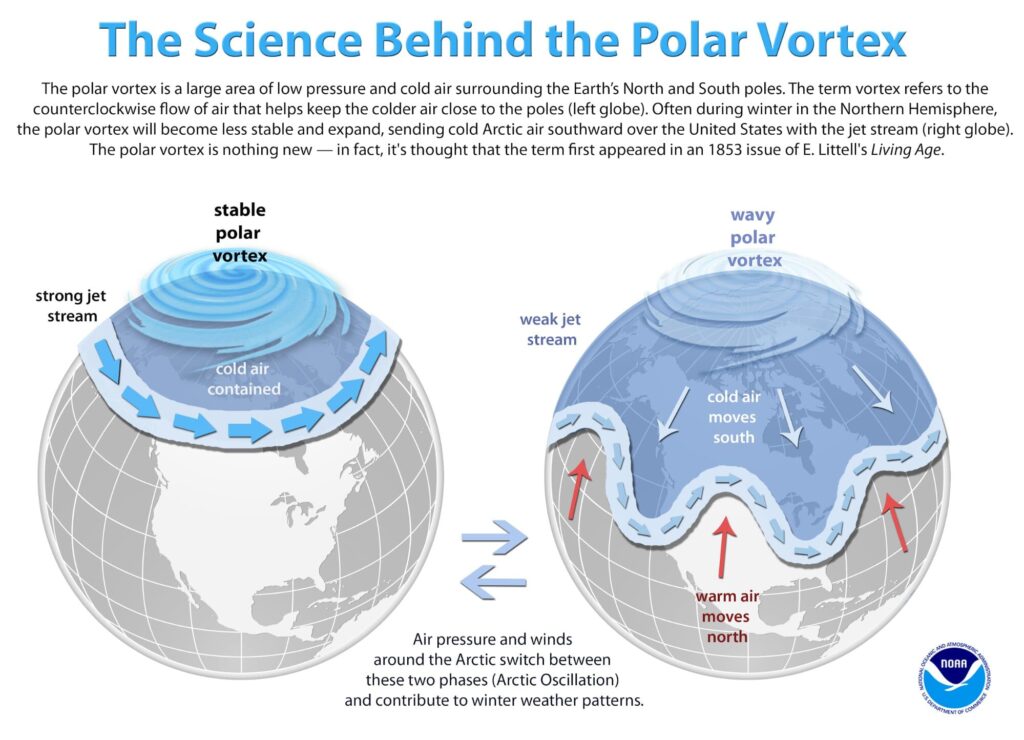

The polar vortex resides within the polar front, the boundary that separates temperate and polar air masses. It remains stationary when the polar jet and westerlies are robust, signifying a substantial temperature contrast between the temperate and polar regions, primarily in winter.

However, when the polar vortex weakens, it can infiltrate mid-latitude areas by altering the general wind flow pattern. This intrusion results in severe cold waves in mid-latitude regions. One of the most notable consequences is the polar vortex cold wave, which can plunge the United States and Canada into sub-zero temperatures, especially in the regions where it predominantly occurs.

Moreover, the polar vortex is intrinsically connected to the depletion of the ozone layer, a complex mechanism

Unveiling the Polar Vortex’s Slippage Mechanism

The movement of the polar vortex is influenced by the behavior of the polar jet, which courses around latitudes of approximately 65º N and S. The jet’s strength is contingent on the temperature contrast between polar and temperate regions. A robust jet exhibits minimal meandering.

Conversely, a weaker temperature contrast causes the jet to meander, generating Rossby waves. These waves result in alternating low and high-pressure cells, with high-pressure cells forming beneath ridges and low-pressure cells beneath troughs. The upper air circulations driven by the jet lead to this configuration.

Intense meandering prompts high-pressure cells to shift northward, displacing the polar cyclone from its typical location, effectively causing it to drift away from the pole into temperate regions. As the jet strengthens and high-pressure cells recede to their customary latitudinal positions, the polar cyclone regains its usual place.